Exploring the Relationships Between Mindfulness, Self-Compassion, and Shame

Abstract

Mindfulness has been proposed as an effective tool for regulating negative emotions and emotional disorders. However, little is known about the relationship between mindfulness and shame. The purpose of the current study was to investigate associations between mindfulness, self-compassion, and shame. One-hundred and fifty-nine participants completed the Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, the Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form, and the Experience of Shame Scale. As expected, both mindfulness and self-compassion were negatively correlated with the experience of shame. In addition, self-compassion was found to fully mediate the relationship between mindfulness and shame. In an effort to explore this relationship further, the associations between specific facets of mindfulness (e.g., observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-reactivity, and non-judgment) and shame were examined. Results showed that the non-judgment facet remains a significant predictor of shame even after controlling for self-compassion. These findings highlight the negative self-evaluative nature of shame, suggesting that shamed individuals may benefit most from interventions that foster non-judgment attitudes toward feelings and thoughts.

Introduction

Shame is undoubtedly one of the unpleasant emotions experienced occasionally by many (B. Brown, 2010). Because of its distressing qualities, humans are often inclined to lessen its intensity. In this study, self-compassion and mindfulness are characterized as adaptive strategies, given their focus on non-judgmental and acceptance attitudes. In the sections below, we discuss these constructs, examine how they might be related, and suggest that self-compassion may mediate the relationship between mindfulness and shame.

Shame

Research suggests that shame is one of the so-called self-conscious emotions (Lewis, 1992; Tracy & Robins, 2004, 2007). It is believed to be an incapacitating emotion that is accompanied by the feeling of being small, inferior, and of “shrinking” (Allan, Gilbert, & Goss, 1994). The self, as a whole, is devalued and considered to be inadequate, incompetent, and worthless (Niedenthal, Tangney, & Gavanski, 1994; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Shame might also involve the feeling of being exposed, condemned, and ridiculed (Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007; Vikan, Hassel, Rugset, Johansen, & Moen, 2010). The phenomenon arises when individuals make internal, stable, and uncontrollable attributions regarding a negative event (Tracy & Robins, 2004, 2007). Although researchers have been exploring shame, the methods by which it could be managed or lessened have received little consideration. The current study investigates this aspect.

Self-Compassion

Self-compassion is a construct derived from Buddhist psychology (Neff & Germer, 2013). It refers to kindness, support, and compassion toward oneself when experiencing personal suffering and pain (e.g., Gilbert, 2009; Neff, 2003a). Neff (2003a, 2003b) postulated that self-compassion has three components: self-kindness versus self-judgment, common humanity versus isolation, and mindfulness versus over-identification.

Self-kindness versus self-judgment refers to treating oneself with kindness and compassion when experiencing failure and pain, as opposed to judging oneself harshly. The dimension of common humanity versus isolation refers to seeing one’s failures and imperfections as part of the wider human experience, instead of feeling isolated. Mindfulness versus the over-identification element of self-compassion refers to taking a balanced view of one’s failures, personal suffering, and self-relevant experiences rather than exaggerating or suppressing them (Neff & Germer, 2013).

Given its inherent characteristics, self-compassion often serves as a shield against negative emotions and anxiety (Allen & Leary, 2010; Neff, 2016). Previous studies have demonstrated that self-compassion is negatively associated with depression (Neff, 2003a), anxiety (Neff, Hseih, & Dejitthirat, 2005; Raes, Pommier, Neff, & Van Gucht, 2011), and neuroticism (Neff, 2009), while it is positively correlated with happiness and positive states (Neff, Kirkpatrick, & Rude, 2007).

Mindfulness

Similar to self-compassion, mindfulness can be viewed as a mode of emotional regulation (Brown & Ryan, 2003). It refers to paying attention to emotions, thoughts, or inner experiences in the present moment without judgment (Kabat-Zinn, 2005). In a mindful mode of processing, individuals approach their moment-by-moment experience with acceptance and openness (Bishop et al., 2004; Kabat-Zinn, 2005). Mindful individuals tend to observe their experiences without overwhelming reaction or elaboration (Crane, 2009); these individuals are open and receptive toward present moment experiences regardless of their valence or desirability (Bishop et al., 2004). Mindful individuals do not make any assumptions or form any beliefs about their experiences; they just observe them as objects with openness and acceptance (Bishop et al., 2004).

To identify the central elements of mindfulness, Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, and Toney (2006) combined all items from the pre-existing measures of mindfulness and performed exploratory factor analysis. The findings indicated that mindfulness comprised five components. These components were as follows: (1) observing—noticing and attending to internal and external experiences, such as bodily sensations, emotions, sound, smell; (2) describing—an ability to express internal experiences with words; (3) acting with awareness—being aware of ongoing behavior or activity; (4) non-judgment of inner experience—taking a non-evaluative stance toward feelings and thoughts; and (5) non-reactivity to inner experience—not reacting to internal and external experiences. Baer et al. (2008) found that these five skill sets are associated with psychological well-being and meditative experiences.

Indeed, studies on mindfulness provide a new perspective on emotional regulation. A causal relationship has been found to exist between mindfulness and wellbeing, especially emotional wellbeing and psychological health (e.g., Bowlin & Baer, 2012; Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007; Keng, Smoski, & Robins, 2011), mindfulness has also been found to negatively correlate with psychological disorders (e.g., Arch & Craske, 2006; Verplanken & Fisher, 2013).

Relationships Between Shame, Self-Compassion, and Mindfulness

Generally, self-compassion and mindfulness might be related to shame as emotion management strategies that offset negative emotions including shame. In this regard, interesting results were found by Kelly, Zuroff, and Shapira (2009). These authors reported that acne sufferers who engaged in self-compassion exercises, such as visualizing a compassionate and accepting image and writing a self-compassionate letter to themselves, showed a reduced level of shame experiences. Indeed, their level of shame decreased to normal levels, which attests to the efficacy of self-compassion.

Consistent with Kelly et al.’s (2009) findings, Gilbert and Procter (2006) demonstrated that evoking compassionate images in the mind and writing compassionate letters to oneself (generating feelings of compassion and warmth) reduced the level of self-threat and shame in clinical patients. Proeve, Anton, and Kenny (2018) also demonstrated that a mindfulness-based therapy could be effective in reducing shame-proneness (a tendency to experience shame) but not external shame (others view “the self” negatively).

Furthermore, Mosewich, Kowalski, Sabiston, Sedgwick, and Tracy (2011) in a cross-sectional study found a significant negative relationship between self-compassion and shame-proneness in young athletes. In a similar vein, Woods and Proeve (2014) investigated the association between mindfulness, self-compassion, shame, and guilt-proneness in a cross-sectional study in a non-clinical population. They reported a negative association between mindfulness and self-compassion with shame. They further conducted a hierarchical regression analysis and showed that shame-proneness was predicted just by self-compassion, not mindfulness.

It thus seems that approaches that embolden resistance to self-attacks and self-criticism are effective in reducing shame, as are strategies based on self-compassion, mindfulness, and acceptance. Since shame and self-criticism are highly associated, interventions that affect one might also influence the other (Kelly et al., 2009).

Could Self-Compassion Be a Mediator of Mindfulness—Shame Association?

It has been assumed that attitudes of compassion toward the self-arise from mindfulness (Neff, 2003b), and that mindfulness training cultivates self-compassion and self-acceptance (Kuyken et al., 2010; Shapiro, Astin, Bishop, & Cordova, 2005; Trich, 2010). Thus, it is not unreasonable to assume that self-compassion mediates the effect of mindfulness. A number of studies provide support for this thesis. For example, Hollis-Walker and Colosimo (2011), in a cross-sectional study, found that self-compassion partially mediated the relationship between mindfulness and psychological well-being. These authors have suggested that “mindfulness cultivates a compassionate attitude, which in turn safeguards against the pernicious effects of negative feelings such as guilt and self-criticism, and facilitates well-being” (p. 226).

Yip, Mak, Chio, and Law (2016) investigated the relationship between self-compassion, mindfulness, and fatigue in a correlational study. They found that therapists who scored higher on a measure of mindfulness experienced less fatigue (burn out and stress) because of their self-compassion tendencies. According to these researchers, self-compassion mediated the association between mindfulness and fatigue. Similarly, Fulton (2018) demonstrated that self-compassion is a mediator of mindfulness and compassion toward others.

In this line of reasoning, Bergen-Cico, Possemato, and Cheon (2013) suggested that the cultivation of self-compassion is an important step, but only comes after mindfulness. The researchers further pointed out that one must cultivate mindfulness skills in order to be able to develop self-compassion as a precautionary strategy against emotional distress. Their study, which enabled them to measure a temporal order in the variables at three waves, suggested that self-compassion evolves through mindfulness and metacognitive activities.

How Is Self-Compassion Different From Mindfulness?

Although as Neff (2003) indicated, while self-compassion has a mindfulness component, it is a conceptually different construct from mindfulness. The mindfulness component of self-compassion suggests that to show compassion toward the self, one must be aware and mindful of personal failure or suffering without trying to suppress or exaggerate them (Neff & Germer, 2013). Furthermore, self-compassion tends to focus on personal sufferings, while the focus of mindfulness is on positive, negative, or neutral experiences. Self-compassion tends to focus on the “self,” whereas mindfulness is more broadly focused on any internal experiences such as emotions, thoughts, or sensations (Baer, Lykins, & Peters, 2012; Neff & Germer, 2013). In the case of lower back pain, for instance, Neff and Germer pointed out that

mindful awareness might be directed at the changing pain and sensations, perhaps noting a stabbing, burning quality, whereas self-compassion would be aimed at the person who is suffering from back pain. Self-compassion emphasizes soothing and comforting the ‘self’ when distressing experiences arise, remembering that such experiences are part of being human (Neff & Germer, 2013, p. 2).

In other words, though one could be mindful of eating a raisin, it is not possible to show compassion toward consuming it (Neff, 2016). Mindfulness is a way of relating to internal experiences, a form of meta-cognition, while self-compassion is about depicting compassion toward the self. One could be mindfully aware of painful thoughts and feelings without comforting and calming the self.

Aims and Hypotheses

The present study is intended to expand previous results and investigate the relationship among shame, self-compassion, and mindfulness. In the current study, three hypotheses are tested. The first hypothesis is that self-compassion is negatively correlated with shame experiences. The second hypothesis is that mindfulness is negatively related to shame experiences. Furthermore, as mentioned above, the literature suggests that mindfulness relates to other constructs through self-compassion. It is interesting to see whether such relationship exists in regard to shame. Therefore, in the third hypothesis, we propose that self-compassion will mediate the relationship between mindfulness and shame. In other words, we test the mindfulness→ self-compassion→ shame model.

In addition, although some studies suggest that when self-compassion and mindfulness are considered together, self-compassion is a stronger predictor of well-being or the experience of negative emotions (Baer et al., 2012; Van Dam, Sheppard, Forsyth, & Earleywine, 2011; Woods & Proeve, 2014). Baer et al. (2006) stated that to understand the relationship between mindfulness and other constructs, it is important to look at mindfulness at subscale levels. Each facet may have a different relationship with different outcome variables. Thus, we aimed to explore how different facets of mindfulness might affect shame and whether self-compassion is a stronger predictor when the facets of mindfulness and self-compassion are considered together in predicting shame.

Method

Participants

One hundred and fifty-nine people (125 female; 33 male, one undeclared), ranging in age from 18 to 65 (M = 27.61, SD = 10.62) participated in this study. The sample included undergraduate students (51.6%), postgraduate students (22.6%), and people who were working full-time (17%), as well as other community members (8.8%). Participants were from the United Kingdom (50.3%), the United States, and Canada (43.4%), and other countries (6.3%).

Procedures

This study was approved by the psychology research ethics committee at the University of the first author (N. S.). Participants were recruited online. The study was advertised on the N. S.’s university’s websites, as well as, two other platforms, namely, www.onlinepsychresearch.co.uk and www.socialpsychology.org. These websites host many research studies and volunteers choose to participate if and whenever they desire. They do not receive any compensation for their participation. Participants gained access to the study through a designated link to a web address. After reading the consent form, participant who wished to participate were asked to complete a series of questionnaires, which are described below.

Measures

The Experience of Shame Scale (ESS)This 25-item scale asks questions about three specific areas (personal characteristics, behavior, and body) about which individuals may feel shame (Andrews, Qian, & Valentine, 2002). Sample questions are “Have you felt ashamed of any of your personal habits?” and “Have you felt ashamed of your body or any part of it?.” Responses were given on a four-point scale (1 = not at all, 4 = very much), with a higher score indicating a higher level of shame. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94.

The short form of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCF-SF)This 12-item scale measures self-compassion with statements such as “I try to be understanding and patient towards those aspects of my personality I don’t like” and “I see my feelings as part of the human condition” (Reas et al., 2010; Neff, 2016). The items are rated on a five-point scale (1 = almost never, 5 = almost always), with a higher score indicating a higher level of self-compassion. The short form has a near-perfect correlation with the long scale of self-compassion (Reas et al., 2010). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90.

The Five-Facet Mindfulness QuestionnaireThis scale consists of 39 items and measures 5 subscales of mindfulness, namely observing (paying attention to sensations and cognitions), describing (ability to label internal feelings), non-judgment of inner experience (being non-judgemental toward feeling and thoughts), non-reactivity to inner experience (let thoughts and feelings come and go without reacting to them), and acting with awareness (being present in the moment) (Baer et al., 2006). The items are rated on a five-point scale (1 = never or very rarely true, 5 = very often or always true), with a higher score indicating a higher level of mindfulness. Cronbach’s alpha was .91 for the total score and ranged from .85 to .93 for the subscales.

Data Analysis

Partial correlations were conducted to test a priori analyses that shame would be negatively associated with mindfulness and self-compassion. Furthermore, to test the third hypothesis, a mediational model was specified using Baron and Kenny’s (1986) approach.

According to Baron and Kenny (1986), four steps are necessary in establishing a mediation: (1) The predictor variable predicts the outcome variable, (2) the predictor variable predicts the mediator, (3) the mediator predicts the outcome variable, and (4) for full mediation: when the mediator and the predictor variable are used simultaneously to predict the outcome variable (a multiple regression), the predictor no longer predicts the outcome variable.

Next, the sobel test and bootstrapping (Preachers & Hayes, 2004) analyses were performed as it is recommended that once the mediation effect was found, it is better to see if its effect is statistically significant mainly by means of these two approaches.

Next, for the exploratory analyses, a multiple regression and a hierarchical regression were conducted. We aimed to explore the associations between specific facets of mindfulness, self-compassion, and shame and to investigate whether mindfulness’ facets add incremental predictive power after controlling for self-compassion.

Results

A Priori Analyses

Associations between demographic variables, shame, mindfulness and self-compassionInitially, the effect of demographic variables (gender, age and nationality) on the experience of shame, self-compassion, and mindfulness was examined. Nationality did not have a significant effect on any of the variables. However, gender was significantly correlated with self-compassion (r = .17, p = .03). Men scored higher (M = 3.17, SD = 0.70) on the self-compassion scale than women, M = 2.80, SD = 0.91; t(156) = -2.54, p = .03. In addition, older participants had higher scores on the mindfulness scale than younger participants (r = .32, p < .001). Therefore, in the following analyses, the effect of age and gender will be controlled for (Table 1).

As expected, partial correlations (controlling for age and gender) showed that shame was negatively and significantly correlated with self-compassion (r = -.60), and mindfulness (r = -.39).

Mediational Analyses

In order for the mindfulness→ self-compassion→ shame model to hold, the following conditions must be met (Baron & Kenny, 1986): (1) mindfulness significantly predicts self-compassion, (2) mindfulness significantly predicts shame, (3) self-compassion significantly predicts shame (while controlling for mindfulness), and (4) mindfulness does not predict shame when controlling for self-compassion.

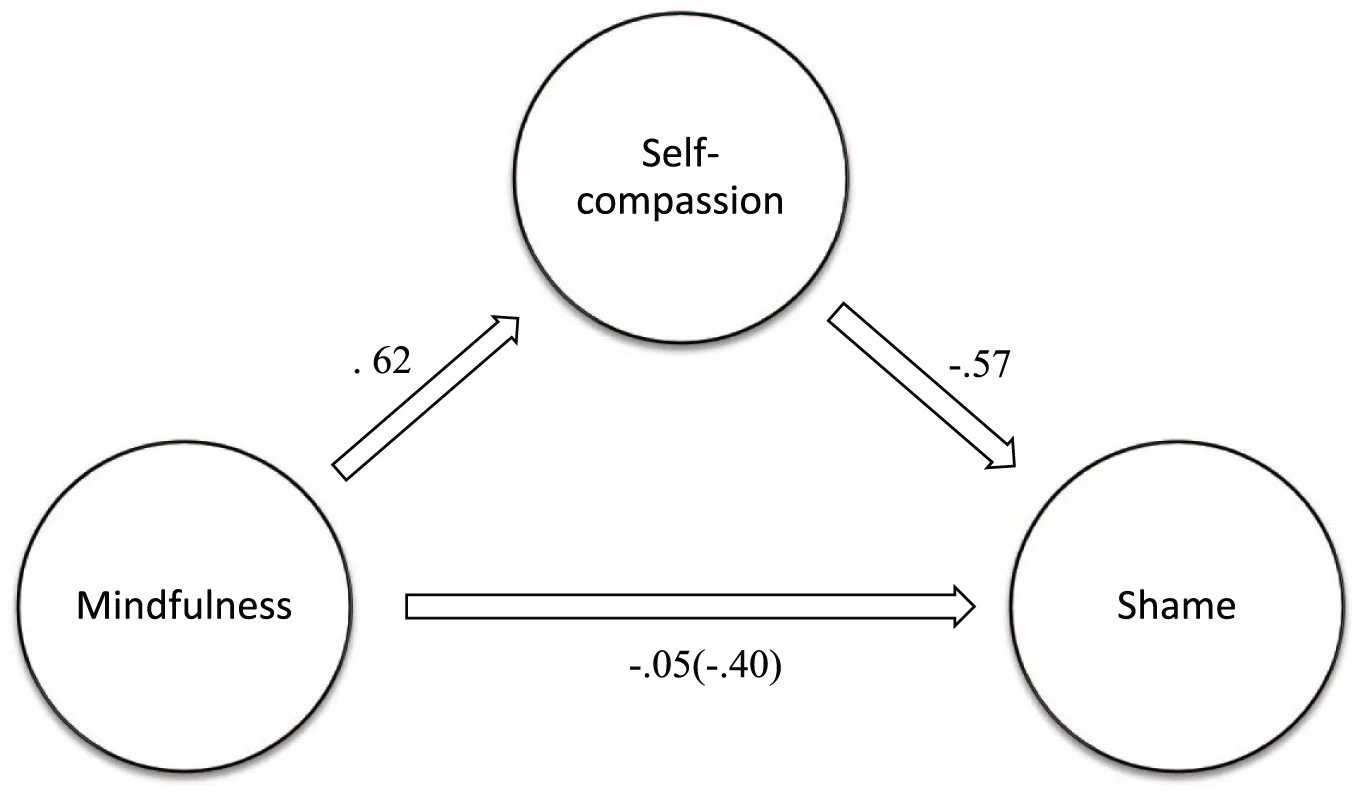

The above model was tested with a set of three regression analyses. In the first regression analysis, mindfulness significantly predicted self-compassion (β = .62, p < .001, ∆R2 = .34, p < .001). In the second regression analysis, mindfulness significantly predicted shame (β = -.40, ∆R2 = .15, p < .001). In the final analysis, a multiple regression was conducted, with mindfulness and self-compassion predicting shame simultaneously. When mindfulness and self-compassion were considered together, self-compassion significantly predicted shame, β = -.57, ∆R2 = .35, p < .001, (t) = -6.87, and mindfulness was no longer a significant predictor of shame, β = -.05, p = .56, (t) = -0.58. These results imply that the relationship between mindfulness and shame is fully mediated through self-compassion1(see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Self-compassion fully mediating the mindfulness-shame relationship.

Note. Values on arrows represent standardized beta coefficients: value within parenthesis is the direct effect of mindfulness on shame.

A bootstrap analysis demonstrated a mediation effect of self-compassion (e.g., Preachers & Hayes, 2004; 95% boostrap confidence interval = -.29; -.25). Bootstrapping was used because it is suitable for smaller sample size and it does not depend on the assumption of normality. A Sobel test (z = -5.76, p < .001) also confirmed that the indirect effect was statistically significant. Both tests thus supported the hypothesis that mindfulness is fully related to shame through self-compassion.

Exploratory Analyses

Next, we investigated the mindfulness construct at the level of its constituting facets. Five factors emerged as reported by Baer et al. (2006), namely observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-reactivity, and non-judgment. Partial correlations of the five factors with shame (controlling for age and gender) were inspected. It was found that shame was not significantly correlated with the observe (r = .06), describe (r = .07), and acting with awareness (r = -.12) subscales. On the contrary, shame was significantly and negatively correlated with the non-react (r = -.27, p < .01) and non-judgment (r = -.47, p < .001) facets. Then, a multiple regression was conducted, regressing shame on the non-react and non-judgment facets of mindfulness and self-compassion. The observe, describe, and acting with awareness subscales were not included because they were not significantly related to shame. It was found that the non-judgment facet and self-compassion significantly predicted shame, while non-react subscale was a non-significant predictor of shame (Table 2).

Then, to investigate whether non-judgment was able to add incremental predictive power after controlling for self-compassion, a hierarchical regression was conducted. Age and gender were entered in the first block, self-compassion in the second block, and the non-judgment facet in the third (Table 3). Both self-compassion and the non-judgment facets accounted for a significant increment in the variance. In particular, the non-judgment factor explained a significant amount of variance after self-compassion was controlled.

Discussion

The primary aims of the current study were to test the three main hypotheses and explore the relationship among mindfulness’ facets, self-compassion, and shame. Although we used a different measure to evaluate the experience of shame, our findings were consistent with previous results (Barnard & Curry, 2012; Mosewich et al., 2011), and indicated that shame was negatively associated with self-compassion. Self-compassion is a mental quality that can be cultivated and enhanced through training (Neff, 2016). Generally, individuals differ in their display of kindness and understanding toward themselves, perceiving oneself isolated in difficult situations, and keeping painful incidents in balanced awareness. These domains of self-compassion are opposed to the main characteristic of shame. They tend to allow individuals to experience less self-condemnation and self-criticism, when a negative event occurs, which is opposite to what it is inherent in the experience of shame.

Furthermore, a negative association between mindfulness and shame was observed, which accords with previous results (Bergen-Cico et al., 2013; Woods & Proeve, 2014). This supports the assumption that mindfulness renders negative emotions less threatening and upsetting, since there is a tendency to observe the experience objectively and without any assumptions or assigning meaning (Bishop et al., 2004). Attention to ongoing experiences in mindfulness is adaptive, without judgment (non-judging) and overwhelming reaction (non-reactivity) (Baer et al., 2008). Contrary to mindfulness, shame is one of the self-conscious emotions that is associated with maladaptive self-focused attention and self-conscious thoughts (Joireman, 2004).

We proposed that self-compassion was a mediator of the mindfulness-shame relationship. In line with our mediation analysis, our findings suggest that self-compassion may fully mediate the relationship between mindfulness and shame. As it is posited in the literature, mindfulness is a broader concept than self-compassion, and it seems that to develop self-compassion, one must have cultivated mindfulness (Bergen-Cico et al., 2013). Our statistical analysis supported this thesis. However, these findings should be interpreted cautiously as our analyses were based on cross-sectional data.

Nonetheless, one interesting aspect of our finding is that when self-compassion and mindfulness were considered together, self-compassion was a stronger predictor of the experience of shame (see also Baer et al., 2012). In other words, self-compassion was more relevant to the experience of shame than mindfulness. The relevant question here therefore is why this happens.

The relationships between the five facets of mindfulness and shame were therefore examined next. When the effect of self-compassion was considered, the only significant predictor of shame was the tendency of individuals to be non-judgemental of inner experience. In fact, the non-judgment facet of mindfulness accounted for a significant incremental amount of the variance over and beyond the effect of self-compassion.

The subscale of “non-judging of inner experience” measures the extent to which individuals take an evaluative stance toward their feelings and thoughts (Baer et al., 2006). Previous studies found that this subscale is related with lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress in comparison to other facets (Cash & Whittingham, 2010), and is mainly responsible for the association between mindfulness and worry (Evans & Segerstrom, 2011).

This was an important result because it confirmed that negative self-judgment is strongly implicated in the experience of shame. Therefore, self-compassion may be more relevant to the experience of shame because it manifests on self-judgment mostly, and more importantly, it may imply that therapies focusing on developing a non-judgemental attitude toward distressing thoughts and feelings might be more beneficial (e.g., Rose, McIntyre, & Rimes, 2018) to protect individuals from the experience of shame. For example, it may be that some form of cognitive therapy which focuses on self-criticism is more favorable for reducing shame than mindfulness-based therapies.

Nonetheless, it should be acknowledged that in the current study mindfulness was measured as an individual difference variable and was conducted in a non-meditating sample. This could be a limitation of this study. It is possible that mindfulness training gives better access to different resources for dealing with emotional difficulties. For example, previous research has demonstrated that the observation facet of mindfulness is strongly related to psychological well-being in participants with mindfulness training, but it is unrelated to well-being in participants with no prior training (Baer et al., 2008).

Similarly, in the current study, the “observe and describe” facets of mindfulness were not significantly correlated with the experience of shame. A similar result was found between being present in the moment and shame. Being present in the moment is an essential element of mindfulness, and most definitions of mindfulness focus on this aspect. Attending to the present moment, rather than ruminating over negative events, helps individuals deal better with negative emotions and difficulties. Acting with awareness was not a significant predictor of shame when the effects of other variables were considered. Nevertheless, as stated earlier, the current study was conducted using a non-mediating sample. It is possible that participants with mindfulness training have access to different resources for dealing with emotional difficulties. Future research is required to confirm these relationships in samples of subjects with mindfulness training.

Another limitation of this study is that, around 70% of participants were university students. University students are not representative of the general population, as they tend to be of a certain age, social class, and intellectual ability. Therefore, the findings from this study may not be generalizable to the wider population.

Furthermore, due to the correlational design, none of these relationships can be assumed to be causal. Indeed, the proposed model can be challenged because the mediation analysis was cross-sectional. Theoretical accounts and research on mindfulness-based therapies indicate that mindfulness training is likely to increase self-compassion (e.g., Kuyken et al., 2010) and mindfulness is a broader concept than self-compassion. Thus, it is rational to presume that mindfulness cultivates self-compassion and self-compassion mediates the relationship between mindfulness and shame. However, as our mediation effect comprised statistical mediation, and cannot prove causality, alternative models cannot be dismissed. This issue could be addressed in future experimental or longitudinal research. In future studies, it might be necessary to explore whether being non-judgemental toward oneself acts as a protective factor in buffering the experience of shame or lessens feelings of shame after they occur. Quite possibly, it is effective in both processes. However, it requires further explorations.

Moreover, although mindfulness and self-compassion are theoretically different concepts (Baer et al., 2012; Neff & Germer, 2013), there are some similarities between the scales used in this study. In particular, the mindfulness scale includes a subscale regarding the non-judging inner experience and contains items such as “I criticize myself for having irrational or inappropriate emotions,” which are similar to items on the self-judgment subscale of self-compassion (e.g., “I’m disapproving and judgmental about my own flaws and inadequacies”). In the current study, self-compassion was measured using the short form of the Self-Compassion Scale, which has 12 items, of which two measure self-judgment. In addition, the correlations among self-compassion, mindfulness, and mindfulness facets (r = .61 for mindfulness and self-compassion: rs ranged from .06 to .64 for the relationships between mindfulness facets and self-compassion) were relatively high. Therefore, the overlap between these two measures is a limitation of this study; future research could address this by employing different measures.

Despite its limitations, the present study makes a valuable contribution to the literature; first, by establishing a link between mindfulness, self-compassion, and shame, and then by suggesting a potential process that underlies this relationship. The experience of shame is usually highly negative, painful, and difficult to manage. Identifying resources that could enhance adaptive functioning and help individuals better deal with emotional experiences is essential. In line with previous studies, this study demonstrates that higher levels of self-compassion, and more importantly non-judgment attitude, are significantly associated with lower levels of shame. In general, interventions that target judgemental attitudes toward the self and promote self-acceptance (e.g., Rose et al., 2018) are likely to be highly beneficial in dealing with both shame and a wide variety of psychological disorders. Specifically, in addition to self-compassion focused therapies, loving-kindness meditation might be constructive for those who suffer from negative self-judgment and shame (Woods & Proeve, 2014). Also, it might be interesting to see whether a therapy focused mainly on non-judgment could be developed to regulate shame; a therapy of this nature might be brief and less complicated to implement.